By Michael Grothaus

To help tackle depression among teens, Britain’s National Health Service wants to meet them on familiar territory: by prescribing them apps.

Depression is the most common type of mental illness, affecting some 350 million people globally and contributing to other problems like obesity, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. But it often goes undiagnosed, and once you know you suffer from it, sometimes the most difficult part of treatment is just being able to regularly sit down on a therapist's couch.

That’s why Britain’s National Health Service has begun encouraging doctors to prescribe people suffering from depression—and teenagers in particular—a thoroughly modern kind of treatment: apps.

Norman Lamb, Minister of State for Care and Support in the U.K., told The Times last week that treatment-by-app was a way of meeting teens on familiar ground.

"If you’re a teenager and your world revolves around digital access, we must make sure you get access to therapy online. So these programs are being developed."

Using Apps To Treat Teenage Depression

The initiative—which involves a doctor prescribing an app alongside medication or face-to-face therapy sessions—is meant, says Lamb, to achieve "a much more seamless service that allows you access online, face to face or over the telephone, whichever is appropriate."

After a diagnosis, a patient may still be given a course of medicine and offered face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy sessions. But under the new program, the doctor also now has the option of medically prescribing an app to help with treatment.

One in 10 British patients are waiting for over a year to be assessed for mental health treatment, according to one study. One in six said they had attempted suicide while on an NHS waitlist.

While Britain's nationalized health system hasn't endorsed a single preferred mental health app, it already recommends a handful of apps that allow patients to assess their moods and set goals and reminders—for medication or therapy sessions—that can be sent via alerts or text messages.

Such tools can be helpful in encouraging patients who may be reluctant to attend face-to-face sessions due to shame or embarrassment, or as a stopgap measure, while patients are waiting for treatment—sometimes for over a year.

A recent report by the U.K. coalition of mental health charities We Need to Talk said that one in 10 patients are waiting for more than a year to be assessed for treatment like cognitive behavioral therapy. One in six—thousands of people across the U.K.—have attempted suicide while on an NHS waitlist for psychological treatment, the report said, and two-thirds said their condition had worsened before they had a chance to see a mental health professional.

Lamb has called these long wait times "unacceptable," and said the health agency would be implementing access and waiting time standards for mental health beginning next year.

The app initiative is part of a broader NHS effort to modernize and enhance youth mental health care in Britain, says Lamb, who has also urged doctors against putting patients on anti-depressants as a "sort of default position."

Though using apps as treatment may sound bizarre to older generations of patients and medical professionals, Lamb is quick to point out that there is firm evidence that app-based therapy has been proven to work in expanding access to treatment and to reducing costs.

A Wall, a Buddy, and Games

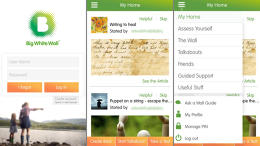

That proof comes from, among other places, a web-based and mobile app calledBig White Wall. The app, launched in 2007 by a British social entrepreneur named Jen Hyatt, is a hybrid of a social network and task manager for people suffering from depression and other mental health issues. The site allows users to post thoughts, drawings, and pictures in an anonymized forum that is moderated 24/7, and to advice from experts online, leave reviews of therapists, and take Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy courses.

The site boasts impressive success rates in helping people deal with their psychological distress, noting that 75% of its members used the site to discuss a mental health issue for the first time in their lives. Eighty percent reported that Big White Wall helped them self-manage their psychological distress, and a staggering 95% of users reported one or more improvements in well-being, according to the company, which also cites peer-reviewed studies on its website. In May it launched a U.S. version.

No comments:

Post a Comment