10 April, 2014

South Somerset’s Symphony project constructs morbidity profiles for a range of long term conditions – showing the true cost and the extent of multi-morbidities. Andrew Street, Panos Kasteridis and Jeremy Martin explain

Many people have complex and ongoing care needs and require support from multiple agencies and various professionals

Since the inception of the NHS, an ever-present challenge has been to improve integration of care within the health and social care system.

Many people have complex and ongoing care needs and require support from multiple agencies and various professionals. But care is often fragmented and uncoordinated, with no one agency taking overall responsibility, so it is often left to individuals and their families to negotiate the system as best they can.

‘It is designed to establish greater collaboration between primary, community, mental health, acute and social care, particularly for people with complex conditions’

In South Somerset, the county council, district hospital, community provider and clinical commissioning group have set up the Symphony project to develop a model of integrated care intended to both improve services and boost efficiency. It is designed to establish greater collaboration between primary, community, mental health, acute and social care, particularly for people with complex conditions.

Colloboration at heart

The project is based on the principle of collaborative care, centred on the needs of individual patients, facilitated by integrated financial arrangements and better pathway management. This means that all of the different organisations involved in delivering services will need to work together to deliver a tailored package of care.

Collaborative working is to be incentivised by a shared outcomes framework, with joint responsibility for all organisations to deliver the outcomes and linked financial structures under an “alliance contract”.

To be able to realise these ambitions, arrangements need to be targeted initially at a subset of the population that would be expected to benefit most from integrated care. We developed broad criteria to identify groups most amenable to integrated care:

- The number in the group needs to form a sufficiently large “risk pool” so that those with high costs are offset by those with low costs.

- To realise savings, initial focus should be directed toward groups for which current expenditure is relatively high.

- Those using services across diverse settings are more likely to be benefit from integrated care.

- There needs should be local consensus that changes to the care pathway are feasible.

We assessed the first three of these criteria by examining patterns of health and social care utilisation and costs for the local population of 114,874 people in 2012. The Symphony project has built a large dataset comprising information about each anonymised individual in the south Somerset population. The dataset has three key features:

- it links acute, primary care, community, mental health and social care data;

- costs are assigned to each individual according to the type of care they have received in each setting;

- demographic characteristics are available for each individual, including age, gender, socio-economic measures, and indicators of morbidity.

Each individual’s morbidity profile is constructed using United Health’s RISC tool used locally to predict unplanned hospital admissions. We identified 49 chronic conditions to construct the morbidity profile of each individual in the population. Individuals can, of course, have multiple chronic conditions.

Multi-morbidity the norm

The data reveals that for people who have a chronic condition it is unusual to have just a single condition: multi-morbidity is the norm, not the exception. Moreover, while it is well known that multi-morbidity increases with age, our analyses demonstrate that it is multi-morbidity not age that most drives health and social care costs. This insight changed the early focus of the Symphony project away from the frail elderly towards adults with multiple long term conditions.

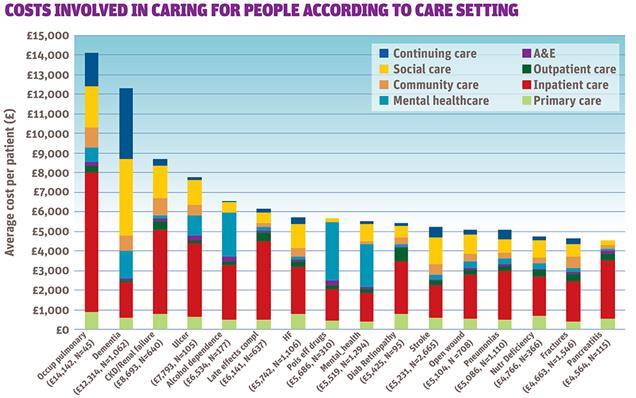

We are also able to look at the annual costs involved in caring for people with particular conditions, according to the different health and social care settings in which they receive care. For example, figure 1 shows average cost broken down by setting for those with a selection of chronic conditions.

The average annual cost for the 45 people with occupational pulmonary disease (OPD) amounts to £14,142, with inpatient costs accounting for the largest proportion. The annual average cost for the 1,062 people with a diagnosis of dementia is £12,314, with the costs of continuing care and social care being most important.

Drilling down further, we can explore the relationship between costs and the number and type of chronic conditions that people have. The accompanying data video illustrates the analyses undertaken for people with diabetes, this being the fifth most prevalent condition in the South Somerset population (5,625 people, five per cent, with total annual costs amounting to £17m. More than 36 per cent of those with diabetes are treated in three or more settings, with inpatient care accounting for the largest proportion of costs (35 per cent), followed by social care (19 per cent) and prescribing (14 per cent).

Out of this 85 per cent of diabetics suffer from at least one other comorbidity and about 35 per cent have three or more chronic conditions. The average annual cost for someone with diabetes alone amounts to about £1,000, but costs increase progressively the more co-morbidities that a person has. We found that the number of conditions is almost as good at explaining costs as markers for particular conditions.

Cost profiles

We constructed similar morbidity and cost profiles for those with hypertension, asthma, diabetes, fractures, coronary artery disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), stroke, dementia, and mental health (other than dementia). These showed multi-morbidity patterns and their relationship with utilisation and costs across health and social care settings. These profiles were shared at a workshop with local health and social care professionals and managers designed to inform the selection of the group.

Following the workshop, further analyses were conducted for those with a diagnosis of diabetes or of dementia. Futher analysis was also conducted for those with a combination of a limited set of comorbidities that local GPs viewed as most significant. These were diabetes, cardiac disease, COPD or OPD, chronic kidney disease or renal failure, depression or anxiety, dementia, stroke and cancer.

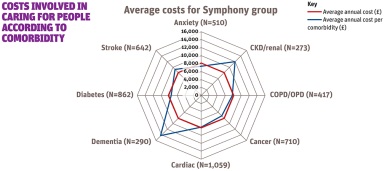

In South Somerset 1,458 people have some combination of three or more these conditions. They are older than the rest of the population (78 compared to 51 years), and have higher average annual costs (£8,152 compared to £1,094. Figure 2 shows the prevalence and costs associated with combinations of conditions among this group.

Figure 2: Average costs per Symphony group

The average annual cost of £8,152 is indicated by the red circle. Costs vary from the average according to particular conditions. Most notably, costs are about £14,000 if dementia is among the conditions and £12,000 if CKD/renal is a co-morbidity, but there is little difference to the overall average for the other conditions.

The project board decided that those with three or more conditions should form the initial cohort. The reasons for this included:

- focusing on multiple conditions avoids Symphony being seen as condition or pathway specific;

- the group of around 1,500 patients offers a reasonable high level of predictable costs variation, provides a sufficiently large risk pool and a more manageable scale than if the focus were solely on diabetes and/or dementia;

- the group incurs costs across all settings, thereby offering the prospect of strengthening links across health, mental health and social care;

- there is an opportunity to reduce inpatient costs, which currently account for 38 per cent of total costs;

- it was felt possible to develop a service for complex patients, while still operating traditional models for those without diabetes or dementia.

Straightforward calculation

The dataset has made it relatively straightforward to calculate the capitated commissioning budget for this group of complex patients. The aim is to start with this initial cohort to demonstrate feasibility and improved outcomes, through the development of personalised care planning and supported self-management.

‘In many parts of the country health and social care data are not combined into a single individual-level dataset’

The hope is to move quickly to a much larger cohort including all patients with long term conditions, using the complex care team as a catalyst to spread a new culture and ethos across the whole health and social care system in south Somerset.

It is a key part of the foundations on which integrated care is being developed in south Somerset. In many parts of the country health and social care data are not combined into a single individual-level dataset.

In those areas where utilisation data have been joined together, information on costs is lacking. In south Somerset analysis of linked data about the use and costs of health and social care for the local population has made it possible to understand existing patterns of care utilisation and to identify for whom and in what way improvements can be made.

Moreover, by maintaining the dataset year on year, it will be possible to assess whether the efforts made to improve integrated care for the local population succeed in realising their ambition.

Andrew Street is professor of health economics; Panos Kasteridis is research fellow at University of York; Jeremy Martin is programme director at the symphony project